- Home

- Thomas Rockwell

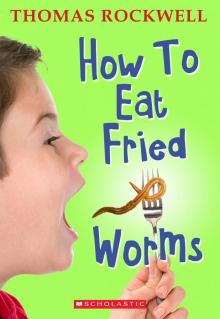

How to Eat Fried Worms

How to Eat Fried Worms Read online

Contents

Title Page

I: The Bet

II: Digging

III: Training Camp

IV: The First Worm

V: The Gathering Storm

VI: The Second Worm

VII: Red Crash Helmets and White Jump Suits

VIII: The Third Worm

IX: The Plotters

X: The Fourth Worm

XI: Tom

XII: The Fifth Worm

XIII: Nothing to Worry About

XIV: The Pain and the Blood and the Gore

XV: 3:15 A.M.

XVI: The Sixth Worm

XVII: The Seventh Worm

XVIII: The Eighth Worm

XIX: The Ninth Worm

XX: Billy’s Mother

XXI: The Tenth Worm

XXII: The Eleventh Worm

XXIII: Admirals Nagumo and Kusaka on the Bridge of the Akaiga, December 6, 1941

XXIV: The Twelfth Worm

XXV: Pearl Harbor

XXVI: Guadalcanal

XXVII: The Thirteenth Worm

XXVIII: Hello, We’re….

XXIX

XXX: The Peace Treaty

XXXI: The Letter

XXXII: Croak

XXXIII: The Fourteenth Worm

XXXIV: The Fifteenth….

XXXV: Burp

XXXVI: The Fifteenth Wo….

XXXVII: Out of the Frying Pan into the Oven

XXXVIII: $ % // ! ? Blip * / & !

XXXIX: The United States Cavalry Rides over the Hilltop

XL: The Fifteenth Worm

XLI: Epilogue

About the Authors

Copyright

I

The Bet

HEY, Tom! Where were you last night?”

“Yeah, you missed it.”

Alan and Billy came up the front walk. Tom was sitting on his porch steps, bouncing a tennis ball.

“Old Man Tator caught Joe as we were climbing through the fence, so we all had to go back, and he made us pile the peaches on his kitchen table, and then he called our mothers.”

“Joe’s mother hasn’t let him out yet.”

“Where were you?”

Tom stopped bouncing the tennis ball. He was a tall, skinny boy who took his troubles very seriously.

“My mother kept me in.”

“What for?”

“I wouldn’t eat my dinner.”

Alan sat down on the step below Tom and began to chew his thumbnail.

“What was it?”

“Salmon casserole.”

Billy flopped down on the grass, chunky, snubnosed, freckled.

“Salmon casserole’s not so bad.”

“Wouldn’t she let you just eat two bites?” asked Alan. “Sometimes my mother says, well, all right, if I’ll just eat two bites.”

“I wouldn’t eat even one.”

“That’s stupid,” said Billy. “One bite can’t hurt you. I’d eat one bite of anything before I’d let them send me up to my room right after supper.”

Tom shrugged.

“How about mud?” Alan asked Billy. “You wouldn’t eat a bite of mud.”

Alan argued a lot, small, knobby-kneed, nervous, gnawing at his thumbnail, his face smudged, his red hair mussed, shirttail hanging out, shoelaces untied.

“Sure, I would,” Billy said. “Mud. What’s mud? Just dirt with a little water in it. My father says everyone eats a pound of dirt every year anyway.”

“How about poison?”

“That’s different.” Billy rolled over on his back.

“Is your mother going to make you eat the leftovers today at lunch?” he asked Tom.

“She never has before.”

“How about worms?” Alan asked Billy.

Tom’s sister’s cat squirmed out from under the porch and rubbed against Billy’s knee.

“Sure,” said Billy. “Why not? Worms are just dirt.”

“Yeah, but they bleed.”

“So you’d have to cook them. Cows bleed.”

“I bet a hundred dollars you wouldn’t really eat a worm. You talk big now. but you wouldn’t if you were sitting at the dinner table with a worm on your plate.”

“I bet I would. I’d eat fifteen worms if somebody’d bet me a hundred dollars.”

“You really want to bet? I’ll bet you fifty dollars you can’t eat fifteen worms. I really will.”

“Where’re you going to get fifty dollars?”

“In my savings account. I’ve got one hundred and thirty dollars and seventy-nine cents in my savings account. I know, because last week I put in the five dollars my grandmother gave me for my birthday.”

“Your mother wouldn’t let you take it out.”

“She would if I lost the bet. She’d have to. I’d tell her I was going to sell my stamp collection otherwise. And I bought that with all my own money that I earned mowing lawns, so I can do whatever I want with it. I’ll bet you fifty dollars you can’t eat fifteen worms. Come on. You’re chicken. You know you can’t do it.”

“I wouldn’t do it,” said Tom. “If salmon casserole makes me sick, think what fifteen worms would do.”

Joe came scuffing up the walk and flopped down beside Billy. He was a small boy, with dark hair and a long nose and big brown eyes.

“What’s going on?”

“Come on,” said Alan to Billy. “Tom can be your second and Joe’ll be mine, just like in a duel. You think it’s so easy—here’s your chance to make fifty bucks.”

Billy dangled a leaf in front of the cat, but the cat just rubbed against his knee, purring.

“What kind of worms?”

“Regular worms.”

“Not those big green ones that get on the tomatoes. I won’t eat those. And I won’t eat them all at once. It might make me sick. One worm a day for fifteen days.”

“And he can eat them any way he wants,” said Tom. “Boiled, stewed, fried, fricasseed.”

“Yeah, but we provide the worms,” said Joe. “And there have to be witnessed present when he eats them; either me or Alan or somebody we can trust. Not just you and Billy.”

“Okay?” Alan said to Billy.

Billy scratched the cat’s ears. Fifty dollars. That was a lot of money. How bad could a worm taste? He’d eaten fried liver, salmon loaf, mushrooms, tongue, pig’s feet. Other kids’ parents were always nagging them to eat, eat; his had begun to worry about how much he ate. Not that he was fat. He just hadn’t worked off all his winter blubber yet.

He slid his hand into his shirt and furtively squeezed the side of his stomach. Worms were just dirt; dirt wasn’t fattening.

If he won fifty dollars, he could buy that mini-bike George Cunningham’s brother had promised to sell him in September before he went away to college. Heck, he could gag anything down for fifty dollars, couldn’t he?

He looked up. “I can use ketchup or mustard or anything like that? As much as I want?”

Alan nodded. “Okay?”

Billy stood up.

“Okay.”

II

Digging

No,” said Tom. “That’s not fair.”

He and Alan and Joe were wandering around behind the barns at Billy’s house, arguing over where to dig the first worm.

“What d’ya mean, it’s not fair?” said Joe. “Nobody said anything about where the worms were supposed to come from. We can get them anywhere we want.”

“Not from a manure pile,” said Tom. “That’s not fair. Even if we didn’t make a rule about something, you still have to be fair.”

“What difference does it make where the worm comes from?” said Alan. “A worm’s a worm.”

“There’s nothing wrong with manure,” said

Joe. “It comes from cows, just like milk.” Joe was sly, devious, a schemer. The manure pile had been his idea.

“You and Billy have got to be fair, too,” said Alan to Tom. “Besides, we’ll dig in the old part of the pile, where it doesn’t smell much anymore.”

“Come on,” said Tom, starting off across the field dragging his shovel. “If it was fair, you wouldn’t be so anxious about it. Would you eat a worm from a manure pile?”

Joe and Alan ran to catch up.

“I wouldn’t eat a worm, period,” said Joe. “So you can’t go by that.”

“Yeah, but if your mother told you to go out and pick some daisies for the supper table, would you pick the daisies off a manure pile?”

“My mother wouldn’t ask me. She’d ask my sister.”

“You know what I mean.”

* * *

Alan and Tom and Joe leaned on their shovels under a tree in the apple orchard, watching the worms they had dug squirming on a flat rock.

“Not him,” said Tom, pointing to a night crawler.

“Why not?”

“Look at him. He’d choke a dog.”

“Geez!” exploded Alan. “You expect us to pick one Billy can just gulp down, like an ant or a nit?”

“Gulping’s not eating,” said Joe. “The worm’s got to be big enough so Billy has to cut it into bites and eat it with a fork. Off a plate.”

“It’s this one or nothing,” said Alan, picking up the night crawler.

Tom considered the matter. It would be more fun watching Billy trying to eat the night crawler. He grinned. Boy, it was huge! A regular python. Wait till Billy saw it.

“We let you choose where to dig,” said Alan.

After all, thought Tom, Billy couldn’t expect to win fifty dollars by just gulping down a few measly little baby worms.

“All right. Come on.” He turned and started back toward the barns, dragging his shovel.

III

Training Camp

SIX, seven, eight, nine, ten!”

Billy was doing push-ups in the deserted horse barn. He wasn’t worried about eating the first worm. But people were always daring him to do things, and he’d found it was better to look ahead, to try to figure things out, get himself ready. Last winter Alan had dared him to sleep out all night in the igloo they’d built in Tom’s backyard. Why not? Billy had thought to himself. What could happen? About midnight, huddled shivering under his blankets in the darkness, he’d begun to wonder if he should give up and go home. His feet felt like aching stones in his boots; even his tongue, inside his mouth, was cold. But half an hour later, as he was stubbornly dancing about outside in the moonlight to warm himself, Tom’s dog Martha had come along with six other dogs, all in a pack, and Billy had coaxed them into the igloo and blocked the door with an orange crate, and after the dogs had stopped wrestling and nipping and barking and sniffing around, they’d all gone to sleep in a heap with Billy in the middle, as warm as an onion in a stew.

But he hadn’t been able to think of anything special to do to prepare himself for eating a worm, so he was just limbering up in general—push-ups, knee bends, jumping jacks—red-faced, perspiring.

Nearby, on an orange crate, he’d set out bottles of ketchup and Worchestershire sauce, jars of piccalilli and mustard, a box of crackers, salt and pepper shakers, a lemon, a slice of cheese, his mother’s tin cinnamon-and-sugar shaker, a box of Kleenex, a jar of maraschino cherries, some horseradish, and a plastic honey bear.

Tom’s head appeared around the door.

“Ready?”

Billy scrambled up, brushing back his hair.

“Yeah.”

“TA RAHHHHHHHHH!”

Tom flung the door open; Alan marched in carrying a covered silver platter in both hands, Joe slouching along beside him with a napkin over one arm, nodding and smiling obsequiously. Tom dragged another orange crate over beside the first; Alan set the silver platter on it.

“A chair,” cried Alan. “A chair for the monshure!”

“Come on,” said Billy. “Cut the clowning.”

Tom found an old milking stool in one of the horse stalls. Joe dusted it off with his napkin, showing his teeth, and then ushered Billy onto it.

“Luddies and gintlemin!” shouted Alan. “I prezint my musterpiece: Vurm a la Mud!”

He swept the cover off the platter.

“Awrgh!” cried Billy recoiling.

IV

The First Worm

THE huge night crawler sprawled limply in the center of the platter, brown and steaming.

“Boiled,” said Tom. “We boiled it.”

Billy stormed about the barn, kicking barrels and posts, arguing. “A night crawler isn’t a worm! If it was a worm, it’d be called a worm. A night crawler’s a night crawler.”

Finally Joe ran off to get his father’s dictionary:

night crawler n: EARTHWORM; esp: a large earthworm found on the soil surface at night

Billy kicked a barrel. It still wasn’t fair; he didn’t care what any dictionary said; everybody knew the difference between a night crawler and a worm—look at the thing. Yergh! It was as big as a souvenir pencil from the Empire State Building! Yugh! He poked it with his finger.

Alan said they’d agreed right at the start that he and Joe could choose the worms. If Billy was going to cheat, the bet was off. He got up and started for the door. He guessed he had other things to do besides argue all day with a fink.

So Tom took Billy aside into a horse stall and put his arm around Billy’s shoulders and talked to him about George Cunningham’s brother’s minibike, and how they could ride it on the trail under the power lines behind Odell’s farm, up and down the hills, bounding over rocks, rhum-rhum. Sure, it was a big worm, but it’d only be a couple more bites. Did he want to lose a minibike over Two bites? Slop enough mustard and ketchup and horseradish on it and he wouldn’t even taste it.

“Yeah,” said Billy. “I could probably eat this one. But I got to eat fifteen.”

“You can’t quit now,” said Tom. “Look at them.” He nodded at Alan and Joe, waiting beside the orange crates. “They’ll tell everybody you were chicken. It’ll be all over school. Come on.”

He led Billy back to the orange crates, sat him down, tied the napkin around his neck.

Alan flourished the knife and fork.

“Would monshure like eet carved lingthvise or crussvise?”

“Kitchip?” asked Joe, showing his teeth.

“Cut it out,” said Tom. “Here.” He glopped ketchup and mustard and horseradish on the night crawler, squeezed on a few drops of lemon juice, and salted and peppered it.

Billy closed his eyes and opened his mouth. “Ou woot in.”

Tom sliced off the end of the night crawler and forked it up. But just as he was about to poke it into Billy’s open mouth, Billy closed his mouth and opened his eyes.

“No, let me do it.”

Tom handed him the fork. Billy gazed at the dripping ketchup and mustard, thinking, Awrgh! It’s all right talking about eating worms, but doing it!?!

Tom whispered in his ear. “Minibike.”

“Glug.” Billy poked the fork into his mouth, chewed furiously, gulped! … gulped! … His eyes crossed, swam, squinched shut. He flapped his arms wildly. And then, opening his eyes, he grinned beatifically up at Tom.

“Superb, Gaston.”

Tom cut another piece, ketchuped, mustarded, salted, peppered, horseradished, and lemoned it, and handed the fork to Billy. Billy slugged it down, smacking his lips. And so they proceeded, now sprinkling on cinnamon and sugar or a bit of cheese, some cracker crumbs or Worcestershire sauce, until there was nothing on the plate but a few stray dabs of ketchup and mustard.

“Vell,” said Billy, standing up and wiping his mouth with his napkin. “So. Ve are done mit de first curse. Naw seconds?”

“Lemme look in your mouth,” said Alan.

“Yeah,” said Joe. “See if he swallowed it all.”

> “Soitinly, soitinly,” said Billy. “Luke as long as you vant.”

Alan and Joe scrutinized the inside of his mouth.

“Okay, okay,” said Tom. “Leave him alone now. Come on. One down, fourteen to go.”

“How’d it taste?” asked Alan

“Gute, gute,” said Billy. “Ver’fine, ver’fine. Hoo hoo.” He flapped his arms like a big bird and began to hop around the barn, crying, “Gute, gute. Ver’fine, ver’fine. Gute, gute.”

Alan and Joe and Tom looked worried.

“Uh, yeah—gute, gute. How you feeling, Billy?” Tom asked.

“Yeah, stop flapping around and come tell us how you’re feeling,” said Joe.

They huddled together by the orange crates as Billy hopped around and around them, flapping his arms.

“Gute, gute. Ver’fine, ver’fine. Hoo hoo.”

Alan whispered, “He’s crackers.”

Joe edged toward the door. “Don’t let him see we’re afraid. Crazy people are like dogs. If they see you’re afraid, they’ll attack.”

“It couldn’t be,” whispered Tom, standing his ground. “One worm?”

“Gute, gute,” screeched Billy, hopping higher and higher and drooling from the mouth.

“Come on,” whispered Joe to Tom.

“Hey, Billy!” burst out Tom suddenly in a hearty, quavering voice. “Cut it out, will you? I want to ask you something.”

Billy’s arms flapped slower. He tiptoed menacingly around Tom, his head cocked on one side, his cheeks puffed out. Tom hugged himself, chuckling nervously.

“Heh, heh. Cut it out, will you, Billy? Heh, heh.”

Billy pounced. Joe and Alan fled, the barn door banging behind them. Billy rolled on the floor, helpless with laughter.

Tom clambered up, brushing himself off.

“Did you see their faces?” Billy said, laughing. “Climbing over each other out the door? Oh! Geez! Joe was pale as an onion.”

“Yeah,” said Tom. “Ha, ha. You fooled them.”

“Ho! Geez!” Billy sat up. Then he crawled over to the door and peered out through a knothole. “Look at them, peeking up over the stone wall. Watch this.”

The door swung slowly open.

Screeching, Billy hopped onto the doorsill!—into the yard!—up onto a stump!—splash into a puddle!—flapping his arms, rolling his head.

How to Eat Fried Worms

How to Eat Fried Worms